Peru commits to bilingualism with a new focus on English

Driven in part by its considerable mineral wealth, the Peruvian economy has seen strong growth in recent years, helping spur outbound student mobility as well as the country’s profile as an emerging sending market. We last reported on Peru in 2014 with a special focus on the University Act enacted that year. Today’s post takes a fresh look at how changes in Peruvian education and the economic landscape continue to impact the student recruitment market.

English proficiency the long-term goal

In 2014, President Ollanta Humala’s administration - which had already passed the University Act and created the National Superintendence of University Education (SUNAU) to oversee the university sector - set the goal of raising the country’s proficiency in English. In the past, the three official languages (Spanish, Quechua, and Aymara) were the focus, but the government has now established a goal to achieve national bilingualism by 2021. "This means implementing a state policy in education so that all our children can manage a foreign language. We will prioritise English," said the President in a 2014 speech. President Humala outlined a plan in which a bilingual education initiative that had been put together originally for the Peruvian armed forces would be expanded to public schools. He adds, "We need qualified and capable people. This is a task to work together both the central governments, private institutions, and communication media. We need schools to assume the challenge to innovate." In order to create a bilingual nation more resources have been marshaled for both student learning and teacher training. In 2016 alone, the goal is to equip 280,000 teachers with dual language skills. The government is particularly focused on 2,010 communities across the country that lack sufficient schooling, with Peru’s second most populous city Arequipa chosen as the flagship municipality for achieving bilingualism first. The government has looked abroad for assistance and, in November 2014, signed a Memorandum of Understanding with the UK, seeking technical expertise in setting up expanded language programmes. UKTI Education and its ELT Working Group, which comprises eight organisations representing most of the UK’s English language providers, will be training Peruvian teachers in the UK and running ELT training schools in Peru. In addition, the UK Higher Education International Unit and the Peruvian Ministry of Education signed an agreement to create postgraduate scholarships for Peruvian students to study in the UK. These are aimed at students with limited economic means, and are funded by Peru's National Programme for Scholarships and Educational Loans (PRONABEC). A wide range of grants are now available in Peru, initiated to develop the English language proficiency of graduates of public universities, to assist both public and private university students in general studies, and to enable studies overseas. For example, the Beca 18 programme awards thousands of scholarships for undergraduate studies, and PRONABEC’s Becas Presidente de la Republica offers grants at the postgraduate level for students heading abroad. Other grants available for overseas studies include offerings from IPFE, La Fundación Universitaria Iberoamericana (FUNIBER), and Fundación Carolina, the latter of which funds more than 500 recipients each year.

Tertiary enrolment and mobility

Out of a population of just over 31 million, roughly 19% of Peruvians are aged 15 to 24, making for a sizeable pool of prospective students. On the whole, approximately 24,000 Peruvian tertiary students were enrolled overseas as of 2011, according to OECD figures, while UNESCO puts the number of tertiary students abroad at 14,204 for 2012, with the top destinations of Spain, the US, Italy, Cuba, France, Brazil, Germany, Australia, Chile, and the UK. The number of Peruvian students attending US institutions has waned in recent years, from a high of 3,771 students ten years ago to 2,763 in 2014/15 (a 6% increase over the year before, however). Meanwhile Peru has increased ties with other countries by lifting visa barriers with various Latin American nations, and by forging education ties outside the region, such as its Erasmus linkages facilitating mobility to EU higher education institutions. Tertiary enrolments within Peru have risen steadily over the past decade with the gross enrolment ratio reaching 40.51% by 2010. Between 2000 and 2010, the number of 19-22 year-olds enrolled more than doubled. Driven by this high demand, Peru experienced a rapid expansion of its private education sector over this period as well. This helped the government achieve goals related to access, however, observers have noted some related challenges as well, including that selectivity in admissions declined, faculty composition shifted toward part-time lecturers away from full-time professors, and the degrees awarded did not correspond to labour market needs.

English language learning in Peru

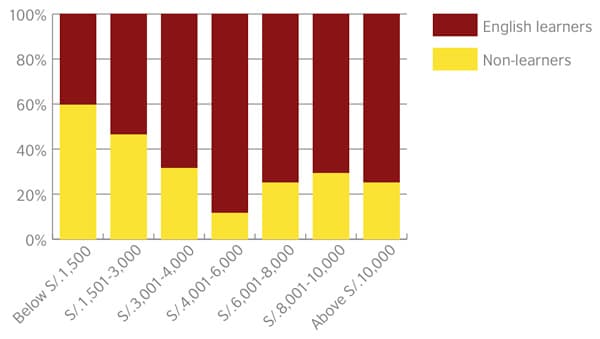

This employability gap may be one reason youth unemployment rates are high - 8.7% for males and 9.1% for females in 2013, compared to the national rate of 3.9%. There is some correlation between English proficiency and employment, as shown in chart below, which reflects survey results from the British Council. Of employed respondents, 71% to 75% of members of the highest income groups were English learners.

Looking forward

Peru has taken some important steps in recent years. It has invested more than US$136 million in science and technology, created fellowships in those fields, and boosted scholarships for Peruvian students at foreign universities. The country is in particular trying to cultivate more STEM graduates to boost key industries such as mining and agriculture. But some changes pushed through during Ollanta Humala’s presidency have not come easily. One of his goals was to confront private universities of low quality. Critics call such schools degree factories producing useless certifications while figures such as Luis Cervantes Liñán - rector of the private University Garcilaso de La Vega - reportedly earn an astonishing US$600,000 per month. President Humala has said succinctly, "The students are being cheated." Yet Peru invests less in public education than its neighbors - only 3.3% of GDP, according to Telesur. Reversals of current policy could occur when national elections take place in April 2016. Due to constitutional term limits, President Humala is unable to seek another term, and the current frontrunner to replace him is fierce critic Keiko Fujimori, daughter of jailed former-president Alberto Fujimori. The younger Fujimori’s comments on President Humala’s policies have been pointed, suggesting that investment in education could be a greater focus in the future. For his part, the President points to "82,000 beneficiaries in scholarships" during his time in office and has called for continuity in education policies, but Ms Fujimori has said she intends to challenge the University Act in court. A major shakeup of the education sector could follow. The major issue in Peru, regardless of who occupies the presidency, will be creating an education system that enables greater economic equity. The tertiary education system is one of the least affordable in the region, and, unless addressed, these financial barriers will continue to hinder equitable access to education in Peru.