Australia ushers in greater private-sector participation in higher education

In 2012, the Australian government removed previously imposed limits on the number of domestic undergraduate students that could be enrolled at public universities. Whereas the previous system was “supply driven” – in the sense that the available spaces were determined by limits on government funding – the new system was “demand driven” and allowed Australian universities to offer additional, government-funded spaces in response to domestic demand. “The new policy was immediately successful in increasing student numbers,” notes a newly released review report commissioned by the Australian government. “Universities offered thousands of new student places in anticipation of the demand driven system. In 2013, the equivalent of 577,000 full‑time students received Commonwealth support in paying their tuition costs, an increase of more than 100,000 on 2009.” The report, Review of the demand driven funding system, offers a wide range of findings and recommendations and concludes “that there is no persuasive case for returning to the ‘capped’ system, and that the demand driven system should be retained, expanded and improved.” This week, the Australian government did just that in a series of education-related announcements contained in the just-released federal budget. In what The Sydney Morning Herald termed “the most radical shake-up to higher education funding” in 25 years, the Coalition government of Prime Minister Tony Abbott will:

- Reduce the share of degree costs covered by public funding by an average of 20%;

- Remove government caps on tuitions;

- Extend direct government support for students enrolled at private-sector institutions and TAFEs (Technical and Further Education institutes) as well as those pursuing diploma and associate degree studies.

Most of the changes announced this week will come into effect in 2016. The debate around funding and the implications for higher education and students in Australia will be in full force in the months and years ahead.

What seems clear, however, is that the Australian government is now moving to deregulate the country’s higher education sector, and to open it to a wider field of providers and partnerships.

The minister abroad

Australian education minister Christopher Pyne foreshadowed this week’s policy and spending announcements during a round of public speaking engagements in the UK at the end of April. “[The review report] concluded that making changes to the demand-driven system will expand opportunities for students, lead to further innovation in courses and modes of delivery, and boost the quality of teaching and graduates. We need all of that,” said the minister. “I am considering the government’s response in the context of the coming Federal Budget, alongside input from our National Commission of Audit… I repeat what I have said before: ours is a deregulatory government."

"I can assure you unreservedly that the coalition government will continue to take steps to set higher education providers free, provide them with more autonomy, and challenge them to map out their futures according to their strengths.”

The significance of the minister’s statement was not lost on the media, among them The Sydney Morning Herald, which concluded, “[Minister Pyne] has given his strongest sign yet that the Abbott government will extend taxpayer funds to for-profit universities in a bid to cultivate a US-style college system in Australia.” Needless to say, the prospects of such a shift have generated considerable debate, particularly among educators. From the perspective of the report authors, however, opening up the system to more providers represents an important step toward greater innovation, diversity, and access in Australian higher education: “The demand driven system has prompted considerable innovation in the public university sector. Much of this comes from using partnerships with other organisations to develop new models of higher education delivery and reach new markets… Despite this progress, the demand driven system could be a stronger driver of higher education innovation and diversity. Inclusion of private higher education providers and TAFEs within the demand driven system in their own right would give greater scope for new models of higher education delivery, and create more competition with the public universities.” The report highlights Australia’s Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency (TEQSA) as a key quality control, recommending that only those providers who are TEQSA-approved (and whose programmes are similarly approved) be eligible to participate in an expanded demand driven system.

Addressing skills shortages

The argument for expanding private sector participation in Australian higher ed appears to be grounded in part in an expectation that private providers would be quicker to adapt to changing labour market conditions.

“The flexibility of the demand driven system in meeting skills shortages is a significant improvement,” says the review report. “The demand driven system can adjust continuously and automatically, without the political risk inherent in waiting for government decisions.”

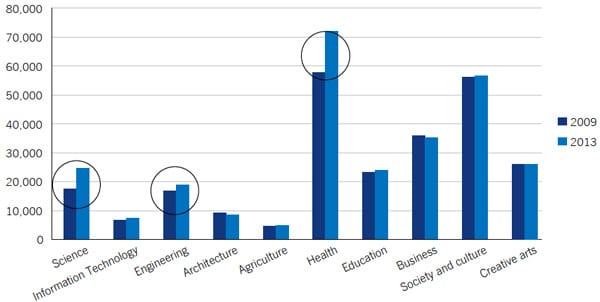

The report’s authors note in particular the increasing enrolment in science, engineering, and health programmes between 2009 and 2013 (see figure below) as indicators of a demand-based system responding to well-established domestic skills shortages in each of these areas.

The review report notes, “Non‑university providers play a major role in delivering pathway programmes into university, reflected in sub‑bachelor courses. Private providers are especially important in the provision of sub‑bachelor courses. Such courses comprise 36% of private higher education provider commencing undergraduate enrolments, compared to 4% in public universities.”

Expanded pathway programmes into public universities, or additional programmes delivered entirely by private providers, may open up a number of new study options in Australia for both domestic and international students. Needless to say, the real opportunities and costs arising from these new policy moves will depend greatly on the further implementation details that will follow the federal budget announcement. For additional background, please see the budget documents and the complete review report on Australia’s demand driven funding system.