Integrating digital technologies at the K-12 level

At ICEF Monitor we have written extensively over the past couple of years on how higher education is changing to reflect the reality of the increasingly Internet-and-technology-driven globalised economy. We have looked at the evolution of MOOCs and of internships, and we have explored the importance of social media channels as a meeting-place for students and institutions. In this post, we turn our attention to the K-12 (Kindergarten to Grade 12) sector: how is it changing as a result of technological advances? What does the future look like at this level? We explore these questions in the knowledge that in some countries – notably China – parents are considering foreign schools at earlier and earlier ages for their children, and will be asking schools and agents the very same questions. We look especially at the US, which is so often at the forefront of educational news, but also at developments in China, a country deeply committed to becoming a world knowledge leader.

Factors influencing the integration of technology in the K-12 sector

How much is technology being used in K-12 schools in various parts of the world? The answer varies from "greatly" to "hardly at all." The reason for the variation is largely a result of four factors:

- Access to technology;

- Government and stakeholders’ prioritisation of and investment in digital technologies;

- The early stage at which we are at in terms of knowing what works and what doesn’t in using technology to improve school-aged children’s learning outcomes;

- Administrators and teachers’ widely diverging comfort levels and belief in technology for K-12 learning.

Access to technology is, of course, the first criterion

In every region and country attempting to figure out the best formula for integrating digital technologies into the classroom, the first step is finding out the current degree of access to computers and the Internet that students and schools have. So that’s just what the European Commission did to fuel an initiative called Opening Up Education, which aims to boost innovation and digital skills in schools and universities. In the course of developing Opening Up Education, the European Commission looked at research that included findings such as the following:

- 63% of nine-year-olds in the EU do not study at a “highly digitally equipped school”;

- Between 50% and 80% of students in the EU never use digital textbooks, exercise software, broadcasts/podcasts, simulations or learning games;

- More than 90% of primary and secondary students in Latvia, Lithuania, and the Czech Republic have Internet access at school, compared to 45% in Greece and Croatia;

- The EU average ratio of primary/secondary school students to computers available for educational purposes is 5:1, but in Greece it’s 21:1;

- In 2009, Denmark became the first country in the world to allow students to use the Internet during national exams.

Obviously, there are substantial differences across the EU in how technology is being used in schools. Findings like the ones above testify to the extent to which access must be addressed before integration strategies can even be considered. In the US, access is much more widespread, with the US National Center for Education Statistics reporting that as far back as 2009, 97% percent of teachers in US public schools had one or more computers located in the classroom every day, and that 93% of these computers had Internet access. The ratio of students to computers in the classroom every day was 5.3 to 1 at that time. More recently, according to eSchool News, more than 50% of US students in grades six through eight have access to a tablet computer, twice last year’s percentage. And this past June, the US government announced a plan to give 99% of the country’s students access to high-speed Internet within five years. Still, even in the US there are challenges with access, and public school districts with more restricted budgets often offer much poorer technology environments than do more well-funded districts or private schools. Moreover, just having access to an Internet-enabled computer does not mean it figures largely in classroom instruction, as we look at next.

Attitudes toward integrating digital technologies in the classroom

Access to digital technologies in K-12 classrooms is one thing; use is another. So even if K-12 students technically could be using digital technologies – thanks to having access to computers and/or other Internet-connected devices in their classrooms – the extent to which they actually are is all over the map, even in the US. A good part of the variation here can be traced to the early stage educators are at in terms of:

- Knowing what the best models are for integrating digital technologies;

- Teachers and administrators’ own comfort levels and attitudes toward technology.

For example, consider this report from the Washington Post on teachers’ feelings about digital technologies as learning aids:

“A Pew Research Center survey found that nearly 90% of teachers believe that digital technologies were creating an easily distracted generation with short attention spans. About 60% said it hindered students’ ability to write and communicate face to face, and almost half said it hurt critical thinking and their ability to do homework. Also, 76% of teachers believed students are being conditioned by the Internet to find quick answers, leading to a loss of concentration.”

Now consider this one, this time from PBS News, which also concerns American teachers’ feelings about digitally enhanced K-12 classrooms:

“Three-quarters of teachers surveyed link educational technology to a growing list of benefits, saying technology enables them to reinforce and expand on content (74%), to motivate students to learn (74%), and to respond to a variety of learning styles (73%). Seven in ten teachers (69%) surveyed said educational technology allows them to 'do much more than ever before' for their students.”

Amid these different attitudes toward the benefits or drawbacks of digitally assisted K-12 learning, a 2012 Project Tomorrow survey of more than 364,000 K-12 students in the US found that:

- 29% of students said they had used an online video to do their homework;

- 41% of students who had not taken a fully online class would like to do so, and cited the top benefit as being able to learn at their own pace;

- 38% of students said they use Facebook to collaborate remotely with other students on class projects;

- 80% of students in grades 9 through 12, 65% in grades 6 through 8, and 45% in grades 3 through 5 use smartphones.

In addition, the US debate as to whether to allow students to use smart phones in class is being decided in favour of the technology. A survey by Bradford Networks revealed that 44% of American K-12 educational institutions allow students to BYOD (Bring Your Own Device). The survey also showed an 89% rate among universities, giving an indication of which way the trend is headed. Among survey respondents at all educational levels, only 6% had no BYOD policy and no plans to implement one.

Teacher education and the emergence of a “hybrid model” may be key

In the US at least, there is an emerging consensus that the way to get more teachers on board, nation-wide, with a technology-positive outlook is by putting forth two interrelated notions and practices: 1. Digital technologies do not – yet – have to displace traditional learning models, but rather complement and enhance them: this is called a hybrid model. The hybrid model sees a blended approach to learning being the most natural shape of K-12 education for the next several years, one which combines the “advantages of online learning combined with all the benefits of the traditional classroom” according to The Clayton Christensen Institute, which offers these examples of hybrid classrooms:

Rotation Model: A programme in which within a given course or subject (e.g., math), students rotate between learning modalities, at least one of which is online learning. Other modalities might include activities such as small-group or full-class instruction, group projects, individual tutoring, and pencil-and-paper assignments. Flipped Classroom: Within a given course or subject (e.g.. math), students rotate on a fixed schedule between face-to-face teacher-guided practice (or projects) on campus during the standard school day and online delivery of content and instruction of the same subject from a remote location (often home) after school. The primary delivery of content and instruction is online, which differentiates a Flipped Classroom from students who are merely doing homework practice online at night. The Flipped Classroom model accords with the idea that blended learning includes some element of student control over time, place, path, and/or pace because the model allows students to choose the location where they receive content and instruction online.

The advantages of the hybrid or blended model is that they appreciate the key role teachers and face-to-face time with students continues to play, while accepting the inevitability and opportunities inherent in digital technology’s coming into the classroom.

The Clayton Christensen Institute predicts that by 2019 half of all high school courses will be delivered online in some form or fashion, and at least 90% of online learning will take place in blended learning environments.

The Institute believes that the hybrid model will continue to characterise most K-12 classrooms in the US for the next several years, as opposed to the “disruptive” model (e.g., MOOCs, or other delivery methods that completely displace traditional ones) that will have more effect in the higher education sector. 2. Schools and teachers can receive professional training and resources that will allow them to feel more comfortable experimenting with different digital models and see what has worked at other schools. Online education company Coursera is staking out a strong position in this respect. The company has launched a new MOOC (presented by the Silicon Schools Fund, the Clayton Christensen Institute, and the New Teacher Center) that aims to show educators some of the latest blended learning techniques being used in various American K-12 schools. Its purpose is “to get educators, technologists, and others interested in blended learning to start innovating by prototyping new models in quick and easy ways.” This comes on the heels of Coursera’s spring 2013 Teacher Professional Development MOOC that also touched on blended learning and included partners such as the American Museum of Natural History, MoMA, the New Teacher Center, and the Commonwealth Education Trust. There are also now K-12 teachers that are giving up their traditional classroom careers in an effort to spearhead the integration of digital technologies into the classroom; you can read here for examples of their new jobs as “ed-tech coaches” or “K-12 technology integrators.” What we can say is that virtually everywhere, including the US, there is a steep learning curve for teachers in terms of using digital technologies successfully in the classroom. The verdict is still out on what will work (i.e., what will produce successful graduates ready and excited for the next stage of their education), but there are case studies that shine a light on emerging best practices – check out this one by Edutopia.

Whatever else, the K-12 arena is heating up

However governments and schools determine the best mix of digitally enabled and traditional learning approaches for K-12 classrooms, ambitious parents of young children will certainly be watching for the schools that do the best job of it, wherever they are. (This is especially true of parents who have participated in online learning themselves and seen the benefits – see here for more.)

ICEF Monitor has already discussed the expansion of elite Western boarding schools to Asia and the perception that attending such schools is a pathway toward acceptance into the best Western universities. And in May, the International Business Times revealed that some Chinese parents are sending their children to MBA preparatory courses… as early as age three. Such offerings have appeared in scores of Chinese cities, and one of them, FasTracKids, has already graduated 100,000 pupils.

This high level of competitiveness is sending increasingly younger students overseas seeking an edge. During the 2010/11 school year, nearly 24,000 Chinese high schoolers were studying in the US, compared to virtually none five years ago. About 6,700 Chinese middle schoolers were enrolled in the US in 2011, up from 65 in 2006.

The New York Times reported that the summer of 2013 saw possibly 100,000 Chinese students, some as young as 10, visit the US as a first step either toward entry into American colleges, or toward obtaining high school degrees.

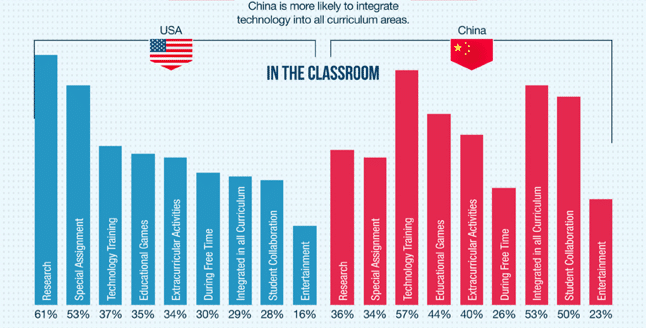

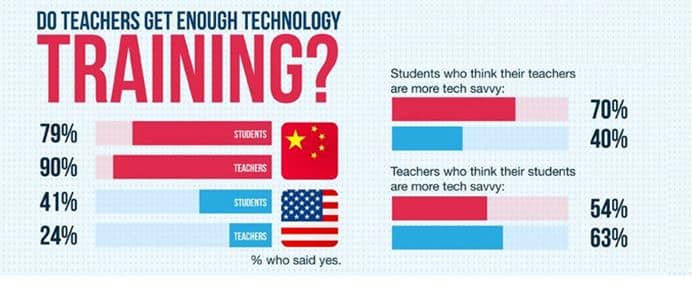

Chinese classrooms have also embraced technology more extensively than their American counterparts. According to the website Edudemic.com, China is more likely to integrate technology into all curricula, Chinese students spend more time using technology in school, and Chinese teachers are more technologically savvy than American teachers. We reviewed more of these findings in a previous post, and an infographic below from Brain Track compares the two countries in specific areas.

It remains to be seen if the US can enter into a new era of improved quality in its public K-12 sector, spurred on by the opportunity of using technology to create robust K-12 learning environments.

In the meantime, private-sector investment in the K-12 arena continues to grow, often with an emphasis on offering unique learning environments designed to attract internationals. Here are just two examples (note the emphases on “global” and cutting-edge technology in their descriptions of their benefits): GEMS: GEMS World Academy (GWA) will open in September 2014 in the Lakeshore East section of Chicago; it will be the first school in the US connected to the GEMS global network of international schools. “GWA Chicago will offer one school, (grades K-12) housed in two state-of-the-art facilities that combine generous classroom space, cutting edge technologies, a planetarium, media centre, fitness centre, a 25-metre swimming pool and a 500-seat auditorium rivaling the top learning centres around the world.” Avenues: Avenues describes itself as a highly-integrated “learning community, and as an international school with 20 or more campuses connected and supported by a common vision, a shared curriculum, collective professional development of its faculty, the wonders of modern technology and a highly-talented headquarters team located in New York City. Collectively, Avenues will comprise a highly-integrated learning community connected through state-of-the-art resources - including superior technology - and a stellar academic leadership team, including longtime heads of Exeter, Dalton and Hotchkiss.” The school opened its first campus last year in New York, with 12 of its planned 15 grades, including all grades between nursery and 9th grade.

Final word

As much as digital technologies are at the forefront of governments, administrators, parents, teachers, and students’ minds when it comes to K-12 education, it is important to remain grounded when looking at how K-12 systems around the world may adapt in response to technology. Consulting firm McKinsey produces reports on why the top school systems in the world, as ranked by the OECD, are successful. Here are the three conditions they found in all the top-ranked school systems:

- They get the right people to become teachers (the quality of an education system cannot exceed the quality of its teachers).

- They develop these people into effective instructors (the only way to improve outcomes is to improve instruction).

- They put in place systems and targeted support to ensure that every child is able to benefit from excellent instruction (the only way for the system to reach the highest performance is to raise the standard of every student).

One “technology integrator,” Krista Moroder, reflects this point – the importance of the teacher in whatever happens in a K-12 classroom - by blogging this opinion:

“We shouldn't look at technology as a replacement for effective teaching; we should look at it as a tool to help us be more efficient with what we are already trying to accomplish. We continuously talk about the future of learning; but what we aren't communicating is HOW to make this happen. We scaffold all of our instruction for our students – how do we scaffold this shift for our teachers?”

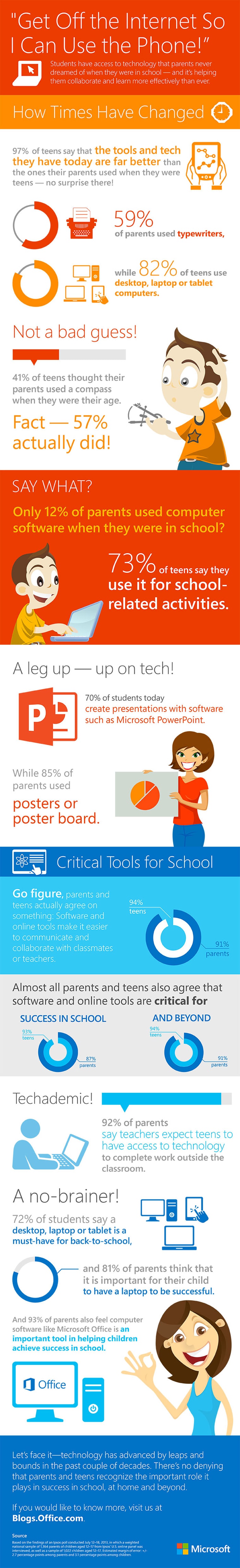

We'll sign off with an infographic comparing educational technologies of the past to the classroom resources of today.