UK to block dependants from accompanying international students as of January 2024

- The UK government will prevent international students from bringing dependants with them beginning January 2024 – unless students are in postgraduate programmes with a research focus

- The move is intended to help curb net migration

- The Graduate Route will not be affected in new immigration restrictions – eligible students will still be allowed 2-3 years to remain in the UK under this route

- Students will not be permitted to switch to the Skilled Worker Route until they complete their programme

- Strategies to deter “unscrupulous” agents from sending students are being developed

- The government says it remains committed to the UK’s International Education Strategy and that the target of attracting 600,000 international students has been met for two years running

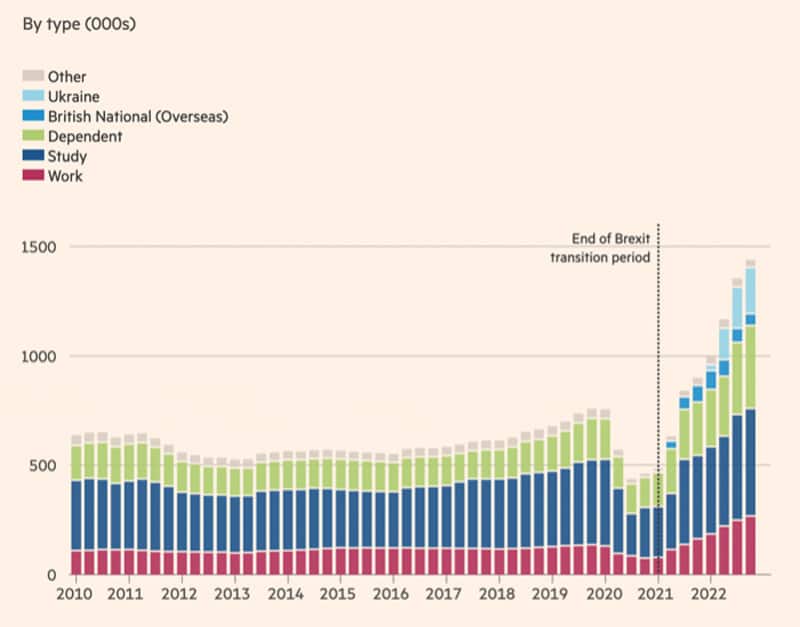

Immigration is at an all-time high in the UK, and the government wants to tighten up the profile of migrants who come to the country and bring down the net migration total. In the period June 2021–June 2022, net migration exceeded 500,000 – more than double the number in 2019, and new data to be released this week is expected to show that the 2022 total has risen by at least 200,000.

Net migration is the difference between the number of people who move to the UK with an intention to stay 12 months or more in a certain period and the number of people who leave during that same timeframe.

There are implications for international students, particularly in the form of a new policy jointly announced by the Home Office and the Department of Education concerning student dependants.

As of January 2024, international students will not be permitted to bring family members with them while they study in the UK – unless they are studying in postgraduate research courses (e.g., research-based PhDs and research-based master’s programmes). International students in postgraduate courses that are not designated as research-oriented will not be permitted to bring dependants.

In 2022, says the Home Office, “almost half a million student visas were issued while the number of dependants of overseas students has increased by 750% since 2019, to 136,000 people.”

Dependants include children under the age of 18, spouses or civil partners, and elderly parents who need long-term care.

Blocking dependants expected to have "tangible" effect

The government describes the new policy as the “single biggest tightening measure a government has ever done,” and Home Secretary Suella Braverman – a relative hardliner on the need to reduce immigration to the UK, says, “We expect this package to have a tangible impact on net migration.” She says the new rule is “the fair thing to do to allow us to better protect our public services, while supporting the economy by allowing the students who contribute the most to keep coming here.”

Ms Braverman also says that international students who are not banned from bringing dependants will nonetheless face a higher burden of proof to show they can “look after themselves and their dependants.”

Education Secretary Gillian Keegan states:

“The number of family members being brought to the UK by students has risen significantly. It is right we are taking action to reduce this number while maintaining commitment to our International Education Strategy, which continues to enrich the UK’s education sector and make a significant contribution to the wider economy.”

Students must stay in student route until programmes are completed

Also announced: International students will no longer be able to obtain a Skilled Worker Visa before their studies have been completed. The rule is intended to discourage international students from choosing the UK predominantly because they want to work there, rather than study. As India’s Economic Times reported last year,

“More and more international students have been opting for [the Skilled Worker route] since it offers a cheaper and faster pathway to full-time employment in the UK. The Graduate Route, on the other hand, requires students to pay expensive course fees and maintenance for the duration of their course, before entering the jobs market.”

The government is shutting down the potential of the Skilled Worker Route being used as a backdoor for non-genuine students determined to find work in the UK.

The impact on one-year master’s students

All undergraduate international students will be prevented from bringing their dependants – but they are not the only ones facing the ban. Those coming for one-year master’s programmes will also be affected. The one-year master’s is a very popular option for Indian and Nigerian students, who are driving the growth of international enrolments in the UK, as well as for all students who must consider affordability when choosing where to study and in which programme. Price-sensitive students are especially likely to be in the very emerging markets coveted by universities across leading destinations.

Diana Beech, chief executive of London Higher, the voice of universities in the UK capital, told University World News:

“The only people set to benefit from the decision to prohibit international masters students from travelling to the UK with their dependants are those in competing major global economies, who will now be rubbing their hands at the prospect of welcoming the talented and ambitious individuals that the UK has effectively turned away.

Evidence shows this decision will also disproportionately affect students from countries such as India and Nigeria, both priority countries in the International Education Strategy, as well as female students, who are more likely to bring dependants with them. For many universities in London, this will mean a significant reduction in annual intake.”

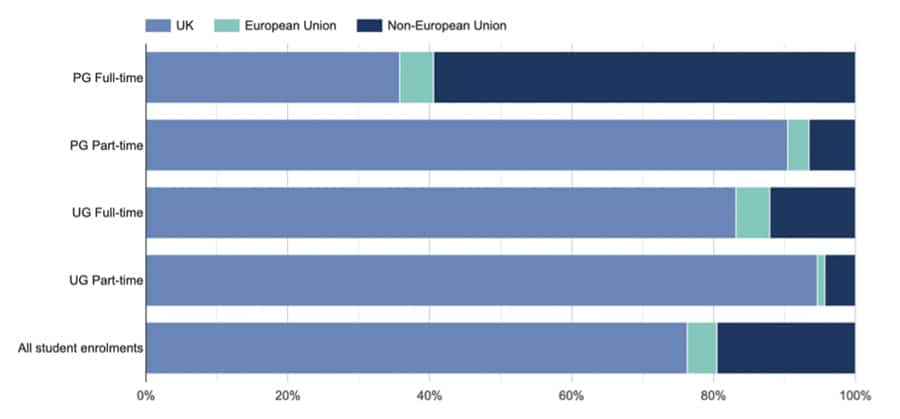

Postgraduate international students, including one-year master’s students, are incredibly important to the revenue of UK universities. Non-EU students are particularly well represented at the postgraduate level, as shown in the chart below. More than 320,000 non-EU students were full-time postgraduate students in 2021/22, versus just over 25,000 EU students and roughly 193,000 UK-domiciled students.

Will the policy be softened?

There is uncertainty about how much flexibility Ms Braverman will allow regarding which students can bring dependants:

“Our intention is to work with universities over the course of the next year to design an alternative approach that ensures that the best and the brightest students can bring dependants to our world leading universities, while continuing to reduce net migration. We will bring in this system as soon as possible, after thorough consultation with the sector and key stakeholders.”

Graduate Route will not be affected at this stage

There was concern last year in international education circles that the Home Office would reduce the time international students could remain in the UK through the Graduate Route from two years to six months. But this feared reduction has not come to pass, and international students will still be able to stay for two years through the Graduate Route (three years for doctoral/PhD students).

Clampdown on agents

The government has also announced that it will “clamp down on unscrupulous international student agents who may be supporting inappropriate applications.” It will be ever-more important for agents to set themselves apart by obtaining professional certifications and establishing a strong track record of success and ethical conduct.

Why are international students targeted?

The economic value of international students in the UK is well documented, but there is rising alarm in some parts of British population about the record pace of migration and what it means for jobs, housing, and the fabric of British society. The chart below shows that international students and their dependants represent an increasing proportion of net migration, as do individuals fleeing from the war in Ukraine.

Only 21% of Britons surveyed this year said they would like to see the number of international students in the country reduced, yet many more want to see immigration curbed (42% as of a separate 2022 Ipsos poll). While the impact of reducing international student dependant numbers will almost certainly be "tangible," it will very likely also make it more difficult for UK universities to attract international students in the coming months.

Industry reaction

Jamie Arrowsmith, Director of Universities UK International, responded to Ms Braverman’s announcement in a measured fashion, but warned that, "Anything that threatens to affect the UK’s global success as a top destination for international talent needs to be considered very carefully.”

"Today’s announcement provides some clarity for students and universities after many months of rumour and speculation but leaves some questions unanswered. The government has reaffirmed its commitment to sustainable growth and to the ambitions set out in the International Education Strategy. Confirmation that the Graduate route will remain open and competitive is critically important. Meaning that international students can remain in the UK and work for up to two or three years after completing their studies, gaining experience and helping to address critical skills shortages.

The rise in the number of dependant visas has been substantial and has likely exceeded planning assumptions in government. We recognise that, in some places, this has led to local challenges around access to suitable family accommodation and schooling, with implications for the student experience. Given this, some targeted measures to mitigate this rise may be reasonable, for example looking at eligibility for particular types of course (such as one-year taught postgraduate programmes) or enhancing the financial assurances that prospective students are required to provide.

While the vast majority of students will be unaffected by proposals that limit the ability to be accompanied by dependants, more information is needed on the programmes that are in scope before a proper assessment of the impact can be made. Yet we do know that any changes are likely to have a disproportionate impact on women and students from certain countries. We therefore urge the government to work with the sector to limit and monitor the impact on particular groups of students – and on universities, which are already under serious financial pressures. The review process that has been announced must consider these issues.”

For more information, please see: