How the pandemic is shaping the expectations and decisions of international students

- Secondary and post-secondary students the world over face unprecedented challenges due to COVID, and understanding these challenges and developing compassionate policies, strategies, and experiences to respond to them is absolutely key for educators and stakeholders going forward

- Affordable and employment-linked education programmes will be even more in demand than they are now

The pandemic is fundamentally shaping the lives of young people belonging to Gen Z (born between 1995 and 2015). Across the world, these young adults are confronted with challenges that include interrupted education programmes, uncertain job prospects, and deteriorating mental health and finances. On top of it all, they face a worsening climate change crisis and a corresponding crisis of confidence in political leadership. It is a lot, to say the least.

Understanding and responding to the changing psychology and emotions of high school and college-aged youth can inform wise choices around programme development, student services, marketing strategy, and coordination with government partners and other stakeholders.

Worries about jobs and income extremely high

The OECD notes that even before the COVID crisis, youth aged 15–29 were 2.5 times more likely to be unemployed than people aged 25–64. As a result of COVID, the organisation warns that,

“Disruption in [this generation’s] access to education and employment opportunities as a result of economic downturn is likely to put the young generation on a much more volatile trajectory in finding and maintaining quality jobs and income.”

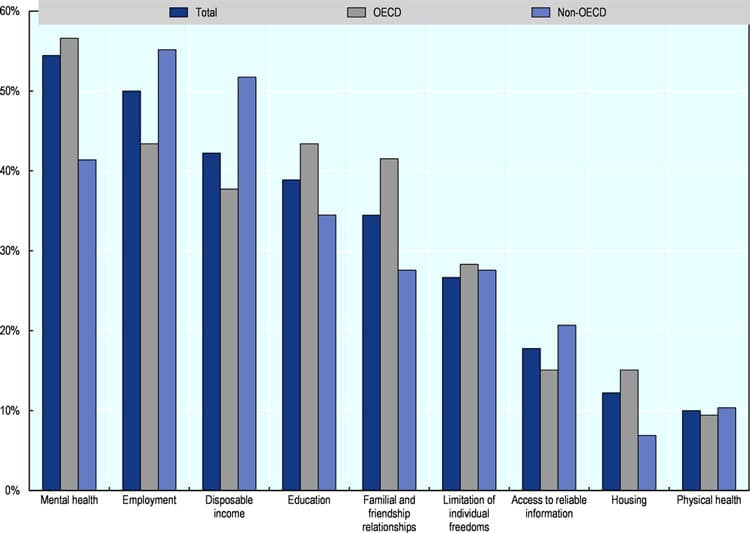

In a survey conducted across 48 countries, the OECD found that youth were far more worried about mental health, income, and employment than about their physical health (see chart below). Despite COVID-related hospitalisation rates rising for this generation, deaths are much lower than in other age groups, and this is not lost on young people looking at the next ten years of their lives and wondering how they will support themselves.

The Financial Times conducted its own global COVID survey and found a high degree of resentment among youth that stems from a belief that the needs of young people are going unaddressed during the crisis in the overarching drive to protect those most at risk from the disease. Take, for example, this comment from one young interviewee from Montreal, Canada:

“We are not in this together, millennials have to take the brunt of the sacrifice in the situation. If you won’t watch out that we don’t end up jobless and poorer, why should we protect you?”

The comment testifies to the pronounced stress affecting many youth who may be more worried about their prospects after the pandemic than about contracting COVID.

Career services have never been more important

We have written extensively over the past few years about students’ rapidly increasing demand for career-oriented programmes. COVID will take this already high demand and push it to a whole other level. As soon as the pandemic eases – and even now, as millions of students anticipate leaving their countries for study abroad in the coming months and years – we can expect a new intensity of interest around:

- Graduate employability stats and testimonials from successful alumni;

- The ability to work while studying;

- Post-graduation work and immigration opportunities;

- Internship opportunities;

- Career counselling resources;

- Scholarships;

- Shorter programmes and upskilling courses.

It's definitely time to think about whether any adjustments in the portfolio of programmes and services your institution offers are needed, as well as the way in which these are presented on the institutional website and in marketing outreach.

Affordability in focus

As well as worrying about future job prospects, students are also dealing with immediate concerns about whether they can afford to study abroad.

Affordability is already a major factor in shaping student flows to destination countries. But during the pandemic there have been disturbing accounts of increasing numbers of international students having to rely on food banks and other relief efforts for their day-to-day needs. An Australian Research Council study reports that in Australia in 2020,

“The free food distribution charity, FoodBank, experienced a 50% increase in demand, much of it driven by international students … the chief executive of the organisation told of a group of students who arrived at one of their distribution points having not eaten for a week.”

The same trend of increased numbers of international students becoming food-insecure has also been observed in Canada, the UK, and the United States.

Many international students have not able to work at all or enough during lockdowns. In many destinations, they have been shut out of federal relief packages to support domestic students. Though some host countries have relaxed work restrictions for international students, it has still been challenging for many students to maintain sufficient income from employment. At the same time, international students are also aware that:

- They are most often paying much higher fees than domestic students;

- They are not having the study abroad experience they expected (e.g., because they are missing out on in-person learning and cultural experiences on campus and in the surrounding community).

The COVID crisis has revealed that international students are often less financially secure than their payment of higher tuition fees might suggest. Moreover, many will be still less secure after COVID recedes and their families take stock of depleted savings.

Being aware of this, and being open to adjusting tuition/fees (and policies, at the governmental level), could well make the difference between attracting students and losing them to other countries/institutions going forward.

Coordination needed for a sustainable, competitive position

Once travel restrictions ease as vaccine rollouts begin to take effect, international students and prospects will feel a dynamic mixture of relief, excitement, and anxiety. They will face economies in various stages of recovery and intense competition for jobs. They will be looking more carefully than ever at national policies enabling them to work during study and to pursue employment after graduation, costs of living (especially accommodation) in destination countries and cities, and scholarship opportunities.

The greater the ability of governments and institutions to coordinate to create compassionate, relevant policies and experiences for COVID-affected international students, the greater will be their ability to compete for these students in a post-pandemic world.

For additional background, please see: