Vaccine breakthroughs lead to updated forecasts for COVID recovery

- Vaccines will be available in early 2021, but it will take several months or longer to achieve widespread immunity

- Various factors will affect how quickly a vaccine can provide immunity in a population, but the rapid progress toward viable vaccines now means that the timeline for COVID recovery is becoming clearer

- More than 80 countries have signed on to an initiative known as COVAX to enable them to obtain more doses of vaccines than would otherwise be possible

COVID-19 continues to ravage people and economies around the globe, but we now know that (at least) three promising vaccines will be available in 2021 to help prevent and lessen the severity of the virus in 2021. This doesn’t mean that the COVID-19 crisis will be over next year, however – especially for some countries. This is due to a number of a number of factors, including:

- Global and domestic inequities that will allow some people, in some regions, to access a vaccine sooner than others;

- Limitations of the vaccines to reduce transmission of COVID;

- Lack of data on how long the vaccines will offer protection for those who have received them;

- Uncertainty about how quickly countries will be able to reach “herd immunity”– which is the point at which an entire population is judged to be resistant to a disease.

As a result, looking into 2021, many experts aren’t predicting an actual “end” to COVID-19. Rather, they anticipate a reduction in the intensity of the crisis, which will allow some countries to begin to return to normalcy and economic recovery. This, of course, would have positive consequences for the international education community.

The psychology of recovery

Herd immunity, which can only be achieved when enough people in a population become immune to a disease due to having been vaccinated or having been previously infected, is not the only factor that will influence when various countries can enter a recovery phase. Recovery will have a psychological dimension as well, says McGill University researcher Jonathan Jarry.

Mr Jarry uses the example of the seasonal flu to illustrate that at a certain point, people will accept a certain mortality rate from a disease in order to resume normal social and economic activity – including travel. Between 290,000 and 650,000 die globally every year from the seasonal flu and associated pneumonia, for example, yet economies and social activities do not grind to a halt as a result.

Given that the mortality rate from COVID next year should go down due to vaccines and emerging drug treatments, more people may begin to accept a level of risk in return for resuming a better quality of life and more financial stability, similar to how they conduct themselves in flu season. This, in turn, will stimulate economies. As more people clamour for normalcy, governments may also respond by relaxing their COVID policies, including border restrictions and other dampers on global commerce. And this, of course, would speed their economic recovery.

As Mr Jarry writes, the psychological dimension will have a profound impact on an overall public decision about whether the COVID crisis is sufficiently – if not totally – over:

“Together, we will have to decide how many deaths from COVID moving forward do we, as a society, consider acceptable…Some of us will never overlook our experiences in 2020 and will continue to wear masks in risky situations. Others will gladly attend sporting events and concerts indoors, their noses and mouths fully exposed. When the proper measures are in place, the pandemic will end one mind at a time.”

Who will get vaccines first?

The UK has just approved the use of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine, and the US and EU countries won’t be far behind. These countries have secured access to vaccines for many reasons including research prowess and financing as well as manufacturing might. As a result, these are the places that also have the potential to achieve herd immunity the fastest.

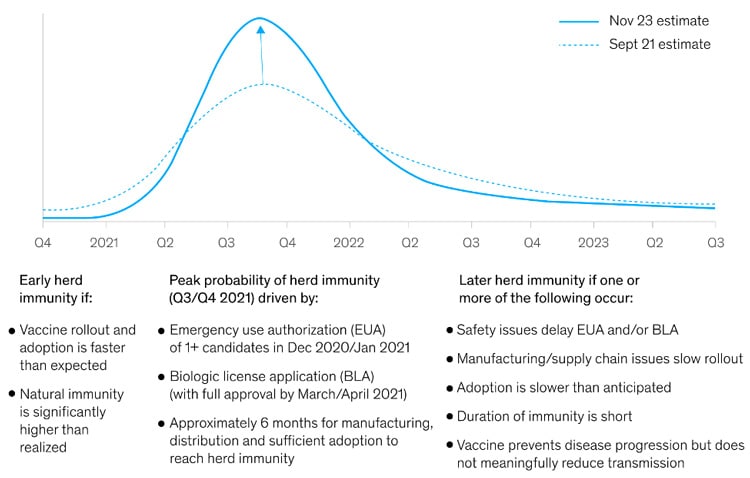

The most recent McKinsey & Company projection for the US is that herd immunity will happen in Q3 or Q4 2021. This projection assumes that 60–70% of Americans will be immune by that time, due mostly to having been vaccinated. If herd immunity takes longer to occur, then we can also expect a social and economic recovery to be slower.

And what of the rest of the world? Unfortunately, Oxfam’s estimate is that 61% of the world’s population won’t have a vaccine until at least 2022. Oxfam notes that “wealthy nations representing just 13% of the world’s population have already cornered more than half (51%) of the promised doses of leading COVID-19 vaccine candidates.”

To help counter the inequities that will determine who gets access to a vaccine in the next couple of years, more than 80 countries have signed onto an initiative called COVAX, which has now received more than US$2 billion in funding. Al Jazeera reports that,

“COVAX aims to pool nations’ purchasing power – and donor funding – to secure a minimum number of affordable vaccines for participating countries through what is called an advanced market commitment. So far, COVAX has secured a possible 700 million potential doses of COVID-19 vaccines, outpacing even the UK, Japan and Canada, according to Duke University."

The goal of COVAX is to obtain two billion vaccine doses by the end of 2021 so that participating countries can immunise up to 20% of their populations. But that still leaves an awful lot of countries and people without a vaccine until 2022.

The three vaccines

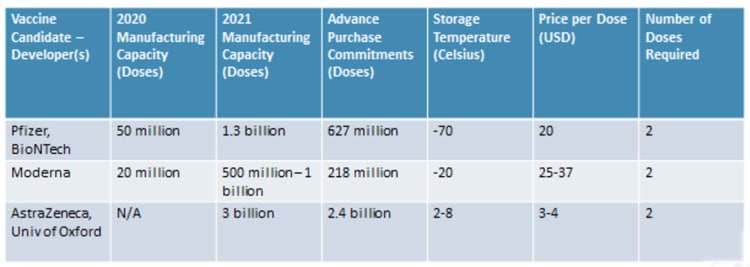

Three pharmaceutical companies so far – Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna, and Oxford-AstraZeneca – are reporting that their vaccine trials are showing incredibly promising efficacy rates. An efficacy rate describes the degree to which a vaccine helps people to fight a disease when they come into contact with it, and the various trials are showing rates as high as 95%.

Additional encouraging news is that none of the trials has produced serious side-effects in those who have received the vaccine. The Pfizer/BioNTech trial is the only trial for which results are final (which has paved the way for its use this month in the UK), but it is certainly reassuring that tens of thousands of volunteers who have received all three vaccines so far have encountered no major side-effects.

Both the high efficacy rates and the apparent safety of the vaccines may also result in a greater number of people willing to be vaccinated than would be the case if the rates were lower and negative consequences more common. This, in turn, may quicken the time it takes for a population to reach herd immunity.

Logistical barriers

Despite this exciting news, massive quantities of the vaccines will be required to cover significant proportions of populations, and until that happens, only high-priority groups such as front-line workers and the elderly will receive their first doses. Beyond that, a key distribution and logistical issue is the temperature at which the various vaccines must be stored. A late-November article by McKinsey & Company notes the following regarding two of the vaccines, based on available data:

“Moderna’s vaccine is stable at refrigerated temperatures (2 to 8 degrees Celsius) for 30 days and six months at –20 degrees Celsius. Pfizer’s vaccine can be stored in conventional freezers for up to five days, or in its custom shipping coolers for up to 15 days with appropriate handling. Longer-term storage requires freezing at –70 degrees Celsius, requiring special equipment.”

Meanwhile, the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine can be “stored, transported and handled at standard refrigerated conditions of between 36 and 46 degrees Fahrenheit for at least six months.” Even though the Oxford vaccine is showing slightly lower efficacy rates than the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, the fact that it does not require the same level of refrigeration represents a key advantage, as it makes it easier and cheaper for the vaccine to be shipped and administered to populations around the world.

Recovery timing

Only one vaccine – for smallpox – has ever eradicated a disease from the world, and this is in large part because smallpox could only infect humans and thus it could only survive by moving to other animal hosts – unlike COVID. Therefore, COVID is expected remain with us as an endemic disease, but it will hopefully end up mutating to become less lethal, and vaccines will help to protect us from it and lessen symptoms if we do get it.

This means that we will have to live with COVID for the foreseeable future – but likely not to the same disruptive extent as in 2020. What many experts believe is necessary to return to normalcy is for as many countries as possible to reach herd immunity in their populations. There are several variables that affect how quickly herd immunity can be achieved, including:

- How speedily a vaccine can be administered to a population (i.e., from approval to manufacturing to distribution across regions, cities, and demographic segments);

- How willing people are to be vaccinated – a major issue since there are currently high levels of resistance in several countries (an Ipsos poll of 18,000 people found that only 54% of French and 64% of Americans would be willing to be vaccinated against COVID);

- Whether people receive the second dose of the vaccine required for immunisation – which requires a high level of logistical coordination not always present in countries, regions, and cities.

Looking into 2021 for international educators

Much remains uncertain in terms of what 2021 will look like for people across the world. Vaccines and more effective antibody treatments have great potential to make it better than 2020. Researchers’ greater understanding of how the virus is spread and what can be done to minimise the risk will make a difference. But insufficient access to vaccines and other treatments in poorer countries may also make 2021 a dangerous and disturbing year – despite every medical advance to combat COVID.

In terms of international education, there is room for optimism. Major destination countries – because of their access to vaccines – will be perceived as safer, and demand for education in these countries will pick up. Improvements will be made to testing and quarantine processes as well as vaccinations for international travellers, which will further ease the current barriers to global travel.

Intra-regional travel for education will also increase, especially in Asia, as groups of countries form travel “bubbles” to stimulate their economies. Bubbles, in theory, happen when countries perceive a certain set of other countries to be sufficiently low risk to open their borders to them under certain conditions. Japan has enacted one such bubble, and Indonesia is trying to form its own.

The flows of international students to various destinations may be quite different in 2021 than we have previously seen. Many international students will look at lower-cost or closer-to-home alternatives to what they had originally planned in terms of institution or even type of credential due to financial instability caused by COVID. But given students’ enduring drive to study abroad – and need for education to propel their careers – we can expect more opportunities for international educators from 2021 on.

For additional information, please see: